During our stay in Aomori-shi, we decided to make a trip to see the Showa Daibutsu at Seiryu-ji temple near Kuwabara.

Thinking it was a big local attraction, featuring as it does on Aomori City guides, including the free tourist map we’d picked up at ASPAM, we presumed that access by public transport would be easy. I knew that we could catch a bus from outside Aomori JR station and that the trip would take around 45 minutes, but didn’t think to check the times the day before we planned to head out there.

We arrived at the bus stop at 10.15. We had missed a bus by around 10 minutes. Now, if this had been a weekday it would not have been a problem. All we would have needed to do was kill time for 90 minutes in town until the next bus at 11.45. As it was, we had decided to go on a Sunday. The 11.45 bus doesn’t run at weekends. The next bus wasn’t due until 1 p.m.

Who would have thought that buses to a tourist attraction would run so irregularly?

A quick look at Google maps (thank goodness for pocket wifi) revealed that we could take a train from Aomori to Koyanagi and then walk for around half an hour to Seiryu-ji.

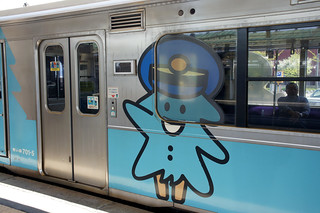

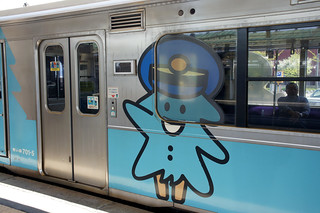

We entered the train station and tried to work out where to catch the train towards Hachinohe. I couldn’t see it anywhere on the electronic boards, so went to the JR ticket office. The helpful woman on the desk told me that we needed to take the Aoimori line, not the JR line. We trooped over to the other ticket office and bought our tickets, then went down to the platform. The train was waiting at the platform, and looked very cute, decorated with the pine tree mascot of the line, who wears a train driver’s hat.

We weren’t the only ones taking photographs, either!

The train journey to Koyanagi took 10 minutes, passing through countryside most of the way. Koyanagi station is a platform without a ticket office or barriers. We didn’t understand the procedure for exiting the train and tried to open the doors closest to us, which were unresponsive. I looked down the carriage and saw the driver/conductor beckoning to us. Other passengers were looking at me as though I was a lunatic, because I carried on pressing the button to open the door as I regarded the beckoning man. Finally it dawned on me that we needed to go out at the door next to the driver’s cab, so that the driver could check our tickets. So, it was a bit like being on a bus.

Once safely off the train, and still the subject of curious stares through the window, we turned pocket wifi on and allowed Google maps to find our location. The view from the single platform was beautiful, with snow-capped mountains in the distance across the small residential area on the other side of the tracks.

We followed Google maps’ guidance and crossed under the railway line, walking towards the buildings you can see above. We soon worked out that this was a dead end and retraced our steps, walking instead alongside a housing estate that reminded me of those you see in Russia, plonked in the middle of nowhere. But much cleaner and more attractive, of course, as we were in Japan!

Past the housing estate, we crossed a level crossing and headed through fields of tall grasses and rice paddies, keeping Totoriyama and Takayama in front of us. We also passed a small orchard and an old man and his grandson tending their rice plants. It was hot and sunny and I was pleased that we had missed the bus and were experiencing this walk through a strange landscape. The walk to Seiryu-ji involved crossing a four lane dual carriageway, which thankfully wasn’t too busy. We crossed behind a man who was carrying a metal bucket. Perhaps he had been fishing in the river.

On the other side of the road we took a side track alongside a small row of houses, and then up past an Inari shrine with straw curtains hanging from the vermilion torii gate. We crossed another road and headed up a hill towards the temple. All of the houses that we passed were modern and had vegetable gardens at the front or alongside. Some of them had apple trees as well.

In a way, it was good to have the guidance of Google maps, because it did mean we knew where we needed to be heading. Unfortunately, Google maps took us past the public entrance to the temple and further up the hill to the monks’ own gate. The gate was open, and we thought it must be the official entrance, so we strolled through. I could see the roof of one of the temple buildings peeping above the brow of the drive.

As we walked along the drive, a monk approached us. My husband thought he was just saying hello, but I could tell that he was barely containing his irritation with us. He admonished us mildly as he firmly closed the gate behind us, explaining that we had come in through a private entrance. He asked whether we had not seen the main entrance a little way back down the road. I explained that I had, but had thought that it was the coach park, and that Google had brought us to his gate. He escorted us through the grounds to the ticket booth, politely telling us that we must buy a ticket before enjoying the temple grounds. He was a little stern.

Once we had paid and picked up our guide leaflet, we followed the prescribed route, visiting the main hall first.

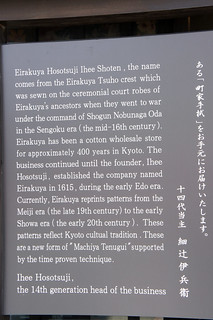

The temple is modern, started in 1982 and completed 10 years later. The main hall is small, with a seated buddha and a couple of bodhisattvas. It is built from local cypress wood, and smells amazing. A passage runs along the back of the altar area and the guide refers to a large painting showing the descent of Amida, but after the telling off we’d had upon entering the grounds, I was too nervous to take a look. Even when another family emerged from the other side. Instead, we went over to the small shop where another monk was doing some photocopying. We bought sandalwood buddha beads as a souvenir, then carried on to the 5 storey pagoda.

The 5 storey pagoda at Seiryu-ji is apparently the tallest wooden pagoda north of To-ji in Kyoto, and is also made from local cypress wood.

We passed along the Green Corridor approach to Showa Daibutsu and caught sight of some pinwheels/windmills dotting the ground beneath the trees.

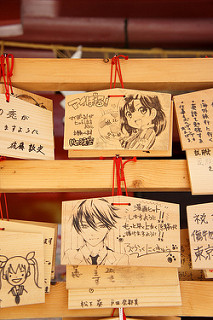

These pinwheels are left by the mothers of unborn children, and line the path to a shrine to Jizo, who sits in a pool with a waterfall behind him.

Opposite Jizo was an altar to Bokeyoke Kannon. At Kannon’s feet sit an old man and an old woman. This particular Kannon is a deity who protects older people who are experiencing problems with their memories. A kind of dementia Kannon, if you like.

I was surprised at how angry this made me feel. My mother has dementia, and I know that there is no protection from it, no cure for it, nothing other than a long, lingering death of the brain and a gradual loss of the person you once knew. My anger stemmed from a sense that this was a religious organisation taking advantage of people’s fears and accepting money and other offerings for a spurious kind of comfort. Bokeyoke Kannon wasn’t the last thing at Seiryu-ji that would make me feel uncomfortable and angry, either.

Before we get to that, though, we were hungry. One of the reasons for visiting Seiryu-ji, as well as the opportunity to see the tallest seated bronze Buddha in Japan, was the promise of vegan shojin-ryori. Traditional buddhist fare, free of animal produce, was served at the Resting Place, or Buddha Buckwheat Shokudo, according to the website. We were looking forward to it. Pausing outside to look at the plastic representations of the food in a small glazed display cabinet, though, we spied the form of tempura shrimp. We thought it was probably a case of only being able to buy plastic representations of tempura that include tempura shrimp. It surely couldn’t be that a Buddhist temple was serving animal produce.

Inside the restaurant, I was feeling the heat so decided to order the zaru soba set, while my husband ordered the Daibutsu set and hoped it wouldn’t have shrimp in it or with it.

We went to sit on the raised tatami seating area next to the window that gave us a view of the valley below. We were the only diners. We drank some free tea and waited for our food. When it arrived, both the zaru soba and the Daibutsu set had, yes you guessed it, tempura shrimp sitting on the side dish behind the other tempura.

The food was good, but didn’t live up to the shojin ryori billing on the website. It was pretty standard fare, nothing unusual about it.

Refreshed by our food, we continued on our way to the Showa Daibutsu. He certainly is an imposing sight as you crest the hill and see him through the trees. I made my husband stand next to the building to get a sense of scale.

Reading the guide’s description of the origins of the Buddha statue was the next thing to make me feel quite cross and very uncomfortable. I wish I had read up on it before, because I don’t think I would have made the trip if I’d known the politics of the temple’s founder. The temple is a very political building. I am not a fan of religion interfering in society outside the realms of that religion’s own followers. I am also not a fan of nationalistic sentiment. I was surprised to find that a Buddhist temple was founded on such nationalistic principles as Seiryu-ji apparently is. According to the guide, the founder Ryuko Oda, had a strong feeling that the Japanese people today, who enjoy an affluent life, should not forget that this is due to the war dead who sacrificed themselves for Japan and laid the foundation for Japan’s affluence. The Showa Daibutsu was inspired by Ryuko Oda witnessing the controversy surrounding visits to Yasukuni Shrine by the incumbent prime minister and thinking that a giant Buddha was just the thing to allow people to pray to the war dead with less controversy. The rest of what appeared to my eyes to be verging on a screed covered moral degeneration arising from the exclusion of religion from the school curriculum, and the need for a symbolic figure to lead the people of Japan in the right direction. None of which compares well with the ethos of another war memorial, in Kyoto, the Ryozen Kannon.

We went inside and looked at a series of scrolls depicting people being tormented in hell by demons, which didn’t sit with either my or my husband’s perception of Buddhism. It felt more akin to mediaeval Catholicism. We even ventured upstairs to the memorial to the War Dead, which was gloomy and made me feel very uncomfortable. There was something about the atmosphere up there that I didn’t like, even though I’m a rational person who doesn’t normally go in for supernatural feelings. I asked if we could leave.

Back outside, we followed the path down through the rest of the temple grounds. We passed the “One Wish” Kannon and Fudo Myo with his sword, rope and flame, and arrived at the shrine to the founder of Shingon Buddhism, Kobo Daishi. I’m quite interested in Kobo Daishi and his attempts to make education accessible to all regardless of means or social status. The shrine consists of a statue of the Daishi in his straw hat, a pond, and a series of 88 stepping stones around the edge of the pond.

The Daishi is known for his teachings on Shikoku, the fourth largest of the Japanese islands, and the pilgrimage circuit of 88 temples dedicated to him. The 88 stepping stones hold sand from each of the Shikoku temples. The guide suggested that walking around the pond, stepping on each of the stones, and saying Kobo Daishi’s name on each one would be a great experience.

Perhaps I wasn’t in the right frame of mind. Perhaps I wasn’t taking it seriously enough. I have to say that it really wasn’t that great an experience. It felt kind of tedious. But maybe that’s the point.

On our way back up the hill, we stopped off again at the “Resting Place” and made ourselves a cup of tea at the outdoor tea kettle.

This was my favourite part of the visit. I found it quite relaxing, taking up a tea cup, ladelling water from the giant tea kettle into the teapot to brew some green tea, and then sipping it while sitting in the shade of the shelter, processing the thoughts that had been stirred up during our visit.

We made a quick visit to the Daishido, and tried to avoid a pretty big hornet that was hanging around the bridge while we put our shoes back on, then we headed back through the fields to Koyanagi.

From Koyanagi, we caught the train again and headed further up the coast to Asamushi Onsen. Again, we didn’t understand the boarding/disembarking procedure, thinking we would have to get on the train by the door near the driver in order to buy a ticket. A teenager getting off laughed at us and pointed to an open door further down the train. It’s good to know that teenagers are the same the world over!

As we got on, we took a ticket from a machine by the door, just like on a Japanese bus. This is a valuable lesson learned, should we ever catch a non-JR local train again in Japan.

I don’t know how I feel about Seiryu-ji. The Showa Daibutsu is stunning to look at, and some of the other buildings in the grounds are also interesting. Overall, though, it felt a bit hostile to me. I didn’t feel as though I should have been there, acting like a tourist. Perhaps it was the initial encounter with the cross monk. Perhaps it was the text in the guide leaflet. I wouldn’t go again. It wasn’t a highlight of the trip.

Maybe if you’re less bothered by things like nationalist sentiment and aggressive expression of religious thoughts, you’ll enjoy it. I don’t know. The couple of hours we spent in Asamushi Onsen (which I’ll blog about separately) were more fun, despite almost everything being closed by the time we got there, and I wish we had spent the whole afternoon there, instead.

So there we are. You live and learn. Not everything in Japan is touched by magic!